Preparing for your biology final requires a strategic approach, encompassing key concepts from ecology to genetics and cellular processes.

Reviewing past quizzes, lecture notes, and utilizing resources like Quizlet will significantly enhance your understanding and exam performance.

Success hinges on understanding population dynamics, enzyme functions, and the diverse classifications within the tree of life.

Mastering these fundamentals will provide a solid foundation for tackling complex biological challenges;

A. Exam Scope and Overview

The biology final exam will comprehensively assess your understanding of core biological principles, spanning multiple units of study. Expect questions relating to ecological concepts like population density calculations and factors influencing population growth, alongside detailed inquiries into community ecology and species interactions.

Cell biology fundamentals are crucial, including distinctions between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, detailed knowledge of cell structures and their functions, and a firm grasp of cellular transport mechanisms. Genetics and heredity will be heavily featured, demanding proficiency in DNA structure, replication, mitosis, meiosis, and Mendelian genetics, including Punnett square analysis.

Furthermore, the exam will cover photosynthesis, cellular respiration, and their interconnectedness, alongside the diversity of life, encompassing organism classification and characteristics of different kingdoms. Be prepared to demonstrate understanding of enzyme structure, function, factors affecting activity, and inhibition. Finally, soil composition, conservation strategies, and the importance of soil health will be evaluated.

B. Importance of Comprehensive Review

A comprehensive review is paramount for success on the biology final, given the breadth of topics covered; Relying on fragmented knowledge will likely result in a lower score; a holistic understanding is essential. Revisiting lecture notes, alongside utilizing review sheets and online resources like Quizlet, will solidify key concepts.

Focus on connecting different biological themes. For example, understand how cellular respiration relates to photosynthesis, or how genetic principles underpin the diversity of life. Don’t simply memorize facts; strive to grasp the underlying mechanisms and relationships.

Prioritize areas where you feel less confident. Identify weak spots through practice questions and targeted review. Addressing these gaps proactively will boost your overall performance and reduce exam-day anxiety. A thorough review isn’t just about recalling information; it’s about building a cohesive understanding of life’s complexities.

C. Study Strategies for Success

Effective study strategies are crucial for mastering the biology final’s extensive material. Begin by creating a detailed study schedule, allocating sufficient time to each topic based on its complexity and your personal understanding. Utilize active recall techniques – testing yourself frequently rather than passively rereading notes.

Practice applying concepts through problem sets and past exam questions. Specifically, work through population density calculations and Mendelian genetics problems. Forming study groups can facilitate discussion and clarify challenging concepts.

Leverage online resources like Quizlet for vocabulary reinforcement and concept review. Break down large topics into smaller, manageable chunks. Finally, ensure adequate sleep and a healthy diet during the study period to optimize cognitive function and exam performance.

II. Ecology and Populations

Focus on population density calculations, factors influencing growth, and the intricate interactions within ecological communities.

Understanding these concepts is vital for success.

A. Population Density Calculations

Population density, a crucial ecological metric, is determined by dividing the total number of individuals within a defined area by that area’s size. This calculation provides insight into how crowded or dispersed a population is, influencing resource availability and competition.

For example, if a forest contains 100 deer spread across 10 square miles, the population density is 10 deer per square mile. Remember to maintain consistent units – if area is in meters, the density will be individuals per square meter.

Understanding this calculation is fundamental, as population density directly impacts factors like disease transmission, mating opportunities, and predator-prey dynamics. Practice applying this formula with various scenarios to solidify your comprehension for the final exam.

Mastering this concept will be essential for analyzing ecological data and predicting population trends.

B. Factors Affecting Population Growth

Several key factors govern how populations expand or contract. Birth rates and death rates are primary drivers, with a higher birth rate leading to growth and a higher death rate causing decline. Immigration – the influx of individuals into a population – adds to growth, while emigration – individuals leaving – reduces it.

Limiting factors, such as food scarcity, predator presence, and disease outbreaks, constrain population growth, preventing exponential increases. These can be density-dependent (impact increases with population size) or density-independent (affect population regardless of size).

Carrying capacity represents the maximum population size an environment can sustainably support, determined by available resources. Understanding these factors is vital for predicting population fluctuations and ecological stability.

Be prepared to analyze scenarios involving these factors on the biology final.

C. Community Ecology: Interactions Between Species

Community ecology explores the intricate relationships between different species within an ecosystem. These interactions are crucial for shaping community structure and dynamics. Competition occurs when species vie for the same limited resources, potentially leading to competitive exclusion.

Predation involves one species (the predator) consuming another (the prey), influencing prey population sizes and driving evolutionary adaptations. Symbiosis encompasses close, long-term interactions, including mutualism (both benefit), commensalism (one benefits, the other is unaffected), and parasitism (one benefits, the other is harmed).

Keystone species exert disproportionately large effects on community structure, and their removal can trigger cascading effects. Understanding these interactions is essential for comprehending ecosystem stability and biodiversity.

Expect questions on the biology final that assess your knowledge of these interspecies relationships.

III. Cell Biology Fundamentals

Cell biology is foundational; focus on prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell distinctions, organelle functions, and transport mechanisms.

Understanding these concepts is vital for success on the biology final exam.

A. Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells

Distinguishing between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is paramount for a strong grasp of cell biology. Prokaryotic cells, like bacteria and archaea, lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. Their DNA resides in a nucleoid region, and they are generally smaller and simpler in structure.

Eukaryotic cells, conversely, possess a true nucleus housing their DNA, along with various organelles such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus. These organelles compartmentalize cellular functions, increasing efficiency. Eukaryotic cells are found in protists, fungi, plants, and animals.

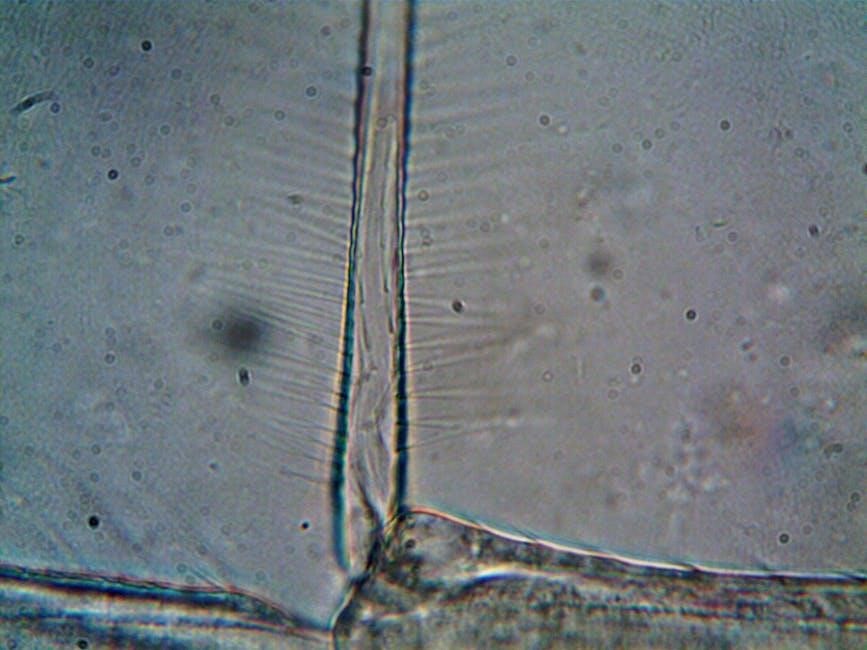

Key differences also lie in cell size, complexity, and modes of reproduction. Understanding these fundamental distinctions is crucial for comprehending the diversity of life and the evolutionary relationships between organisms. Reviewing diagrams and comparing structural features will solidify your understanding for the final exam.

B. Cell Structures and Their Functions

A comprehensive understanding of cell structures and their respective functions is essential for success on the biology final. The nucleus controls cellular activities, while ribosomes synthesize proteins. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the cell, generating ATP through cellular respiration.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) plays a role in protein and lipid synthesis, and the Golgi apparatus processes and packages these molecules. Lysosomes contain enzymes for intracellular digestion, and vacuoles store water and nutrients. The cell membrane regulates the passage of substances in and out of the cell.

Plant cells also feature chloroplasts for photosynthesis and a cell wall for structural support. Familiarize yourself with the location and roles of each organelle to effectively answer exam questions. Visual aids and detailed diagrams will prove invaluable during your review process.

C. Cellular Transport Mechanisms

Mastering cellular transport mechanisms is crucial for a strong performance on the biology final. Passive transport, including diffusion and osmosis, doesn’t require energy expenditure, moving substances down their concentration gradients. Facilitated diffusion utilizes membrane proteins to aid this process.

Active transport, conversely, requires energy (ATP) to move substances against their concentration gradients. This includes processes like the sodium-potassium pump. Endocytosis involves the cell engulfing materials, while exocytosis releases substances to the exterior.

Understanding the differences between these mechanisms – and how factors like concentration and membrane permeability influence them – is key. Review examples of each transport type and their biological significance. Practice identifying scenarios requiring specific transport methods for optimal exam preparation.

IV. Genetics and Heredity

Focus on DNA structure, replication, mitosis, meiosis, and Mendelian genetics. Punnett squares are essential for predicting inheritance patterns and understanding genetic variations.

A. DNA Structure and Replication

Understanding the double helix structure of DNA is paramount. Recall that DNA comprises nucleotides – each containing a deoxyribose sugar, a phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base (Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, Cytosine). Adenine pairs with Thymine, and Guanine pairs with Cytosine, forming the ‘rungs’ of the ladder.

Replication is a crucial process for cell division. It begins with unwinding the DNA double helix, creating a replication fork. DNA polymerase then adds complementary nucleotides to each strand, following base-pairing rules. This results in two identical DNA molecules, each with one original and one new strand – a process known as semi-conservative replication.

Pay attention to the roles of key enzymes like helicase and ligase. Helicase unwinds the DNA, while ligase joins the DNA fragments. Accurate replication is vital to prevent mutations and ensure genetic integrity during cell division.

B. Mitosis and Meiosis: Cell Division Processes

Mitosis is essential for growth and repair, resulting in two identical daughter cells. The phases – Prophase, Metaphase, Anaphase, and Telophase (PMAT) – must be memorized. During mitosis, chromosomes are duplicated and then separated equally into the two new nuclei, maintaining the original chromosome number.

Meiosis, conversely, produces gametes (sex cells) with half the chromosome number. It involves two rounds of division (Meiosis I and Meiosis II), resulting in four genetically unique haploid cells. Crucially, crossing over occurs during Prophase I, increasing genetic diversity.

Distinguish between the outcomes of each process. Mitosis creates clones, while meiosis generates variation. Understanding the role of each process in sexual reproduction and its contribution to genetic diversity is key for the final exam.

C. Mendelian Genetics and Punnett Squares

Mendelian genetics explores inheritance patterns based on Gregor Mendel’s experiments with pea plants. Key terms include alleles, dominant and recessive traits, genotype, and phenotype. Understanding these definitions is fundamental to predicting inheritance outcomes.

Punnett squares are diagrams used to visualize all possible combinations of alleles from parents. They help determine the probability of offspring inheriting specific traits. Practice constructing and interpreting Punnett squares for monohybrid and dihybrid crosses.

Master concepts like homozygous, heterozygous, and test crosses. Be prepared to solve problems involving incomplete dominance and codominance. A strong grasp of these principles will be crucial for success on the genetics section of the biology final exam.

V. Photosynthesis and Cellular Respiration

Focus on the interconnectedness of these processes: photosynthesis captures light energy, while cellular respiration releases it from food.

Understanding their relationship is vital for exam success.

A. Photosynthesis: Capturing Light Energy

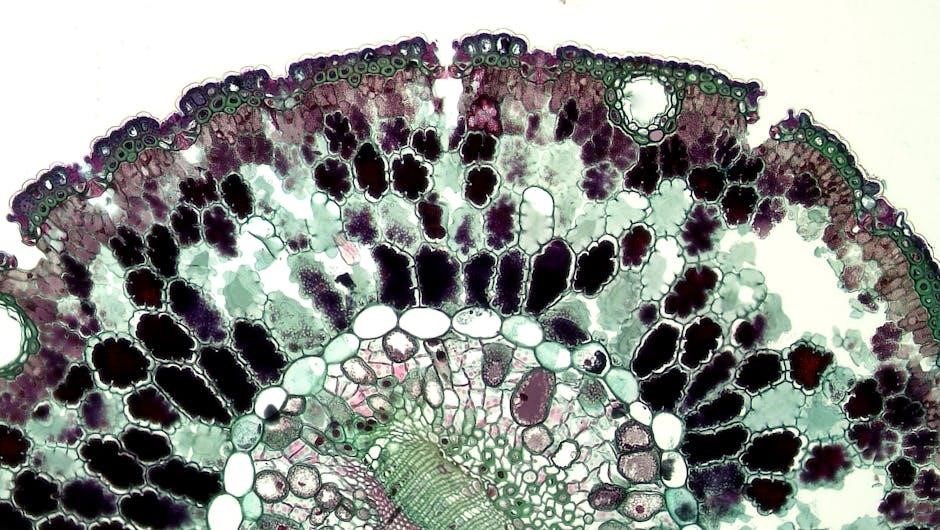

Photosynthesis is the remarkable process by which plants, algae, and some bacteria convert light energy into chemical energy in the form of glucose. This process is fundamental to life on Earth, providing the primary source of energy for most ecosystems;

Key components include chlorophyll, the pigment that absorbs light, and chloroplasts, the organelles where photosynthesis takes place. The process can be broadly divided into two stages: the light-dependent reactions and the light-independent reactions (Calvin cycle).

The light-dependent reactions occur in the thylakoid membranes and utilize light energy to split water molecules, releasing oxygen as a byproduct and generating ATP and NADPH. The Calvin cycle, occurring in the stroma, uses ATP and NADPH to convert carbon dioxide into glucose. Understanding these stages, the inputs, and the outputs is crucial for the exam. Remember to review the role of different wavelengths of light and their impact on photosynthetic rates.

B. Cellular Respiration: Releasing Energy from Food

Cellular respiration is the process by which cells break down glucose to release energy in the form of ATP. This energy fuels cellular activities, enabling organisms to function. It’s essentially the reverse of photosynthesis, utilizing oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide and water.

The process unfolds in four main stages: glycolysis, pyruvate oxidation, the Krebs cycle (citric acid cycle), and the electron transport chain. Glycolysis occurs in the cytoplasm, breaking down glucose into pyruvate. The subsequent stages take place within the mitochondria.

The Krebs cycle further oxidizes pyruvate, generating ATP, NADH, and FADH2. The electron transport chain utilizes these electron carriers to create a proton gradient, driving ATP synthesis through oxidative phosphorylation. Understanding the role of each stage, the inputs, and outputs is vital. Don’t forget to study anaerobic respiration (fermentation) as an alternative pathway!

C. Relationship Between Photosynthesis and Respiration

Photosynthesis and cellular respiration are fundamentally interconnected processes, forming a vital cycle for life on Earth. Photosynthesis utilizes light energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen, effectively storing energy. Conversely, cellular respiration breaks down glucose using oxygen to release energy, producing carbon dioxide and water as byproducts.

Essentially, the products of photosynthesis are the reactants of cellular respiration, and vice versa. This creates a continuous flow of energy and matter within ecosystems. Plants perform both processes – photosynthesis to create food and respiration to utilize it for growth and maintenance.

Understanding this reciprocal relationship is crucial. Photosynthesis captures energy, while respiration releases it. This interdependence highlights the delicate balance within biological systems and the cyclical nature of life’s essential processes.

VI. Diversity of Life

Explore the vast spectrum of organisms, categorized into kingdoms – Prokaryota, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia – understanding their unique characteristics and reproductive strategies.

A. Classification of Organisms

Understanding the hierarchical system of biological classification is crucial. This system, ranging from broad domains to specific species, organizes the incredible diversity of life on Earth. Initially, organisms were grouped into five kingdoms – Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia – but modern classification, based on evolutionary relationships, often utilizes a three-domain system: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya.

Within each domain, organisms are further categorized into kingdoms, phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and finally, species. Key characteristics used for classification include cellular structure (prokaryotic vs. eukaryotic), mode of nutrition (autotrophic vs. heterotrophic), and reproductive strategies (sexual vs. asexual).

Recognizing the evolutionary connections between organisms, represented in phylogenetic trees, is essential. These trees illustrate the shared ancestry and divergence of different species, providing a framework for understanding the relationships within the tree of life.

B. Characteristics of Different Kingdoms (Prokaryota, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, Animalia)

Prokaryota (Bacteria & Archaea) are unicellular, lacking a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles. They exhibit diverse metabolic strategies. Protista are a diverse group of mostly unicellular eukaryotes, some autotrophic, others heterotrophic.

Fungi are eukaryotic, heterotrophic organisms that obtain nutrients through absorption, often as decomposers. They possess cell walls made of chitin. Plantae are multicellular, autotrophic eukaryotes utilizing photosynthesis, with cell walls composed of cellulose. They are vital producers in ecosystems.

Animalia are multicellular, heterotrophic eukaryotes lacking cell walls. They obtain nutrients through ingestion and exhibit complex tissue organization and movement. Understanding these fundamental differences – cellular structure, nutrition, and organization – is key to differentiating between kingdoms. Recognizing examples within each kingdom solidifies comprehension.

C. Sexual and Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction involves a single parent and results in genetically identical offspring, utilizing processes like budding, fission, or fragmentation. This method is efficient for rapid population growth in stable environments. Sexual reproduction, conversely, involves the fusion of gametes from two parents, generating genetic diversity through meiosis and fertilization.

This diversity is crucial for adaptation and evolution. Key differences include the number of parents, genetic variation in offspring, and the role of meiosis. Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of each reproductive strategy is vital.

Consider how environmental factors influence the prevalence of each method. Knowing terms like autotrophic and heterotrophic, alongside these reproductive strategies, will be essential for exam success.

VII. Enzymes and Biochemical Reactions

Enzymes accelerate reactions by lowering activation energy; factors like temperature and pH impact their activity.

Inhibition, whether competitive or non-competitive, alters enzyme function and reaction rates.

A. Enzyme Structure and Function

Enzymes are biological catalysts, primarily proteins, that significantly speed up biochemical reactions within cells. Their structure is crucial to their function; enzymes possess an active site, a specific region where substrates bind.

This interaction follows a “lock-and-key” or induced-fit model, ensuring specificity. Enzymes aren’t consumed in reactions, allowing them to catalyze repeatedly. They lower the activation energy required for a reaction to occur, accelerating the process without altering the equilibrium.

Understanding enzyme structure – including primary, secondary, tertiary, and sometimes quaternary structures – is vital. Denaturation, caused by factors like temperature or pH changes, can disrupt this structure and render the enzyme inactive. Proper enzyme function is essential for all life processes.

B. Factors Affecting Enzyme Activity

Several factors profoundly influence enzyme activity, impacting their catalytic efficiency. Temperature plays a critical role; increasing temperature generally boosts reaction rates up to an optimal point, beyond which denaturation occurs, drastically reducing activity.

pH also significantly affects enzyme function, as changes can alter the ionization of amino acid residues within the active site, disrupting substrate binding. Substrate concentration influences reaction velocity – initially, increasing substrate concentration enhances activity, but eventually reaches a saturation point.

Enzyme concentration directly correlates with reaction rate, assuming sufficient substrate is present. The presence of inhibitors, competitive or non-competitive, can also modulate enzyme activity, hindering or blocking substrate binding. Understanding these factors is crucial for comprehending biological regulation.

C. Enzyme Inhibition

Enzyme inhibition is a crucial regulatory mechanism in biological systems, controlling metabolic pathways. Competitive inhibition occurs when a molecule structurally similar to the substrate binds to the active site, preventing substrate attachment. This is often reversible by increasing substrate concentration.

Non-competitive inhibition, conversely, involves a molecule binding to a different site on the enzyme (allosteric site), altering its shape and reducing catalytic efficiency. This type of inhibition isn’t overcome by adding more substrate.

Understanding these mechanisms is vital, as many drugs and toxins function as enzyme inhibitors. Irreversible inhibition involves a permanent bond forming between the inhibitor and the enzyme, effectively disabling it. Analyzing inhibition patterns helps elucidate enzyme function and metabolic control.

VIII. Soil Formation and Conservation

Soil health is paramount for ecosystems; its composition includes layers and organic matter. Conservation strategies, like reducing erosion, are vital for maintaining fertile land.

A. Soil Composition and Layers

Understanding soil composition is crucial; it’s a complex mixture of mineral particles, organic matter, water, and air. These components interact to support plant life and overall ecosystem health. Soil isn’t uniform; it develops distinct layers known as horizons.

The O horizon is the uppermost layer, rich in organic material in various stages of decomposition – leaf litter, for example. Below that lies the A horizon, often called topsoil, which is dark and fertile due to accumulated organic matter (humus). The B horizon, or subsoil, accumulates minerals leached from the A horizon, but contains less organic matter.

Finally, the C horizon consists of weathered parent material – bedrock that has begun to break down. The R horizon represents the bedrock itself. Each layer’s characteristics influence water drainage, nutrient availability, and root penetration, impacting plant growth and the entire ecosystem. Knowing these layers is essential for understanding soil health and conservation.

B. Soil Conservation Strategies

Protecting our soil resources is paramount, as erosion and degradation threaten agricultural productivity and ecosystem health. Several strategies can mitigate these issues, ensuring long-term soil sustainability; Contour plowing, for instance, involves plowing across the slope of the land, reducing water runoff and erosion.

Terracing creates step-like platforms on steep slopes, slowing water flow and preventing soil loss. Crop rotation involves alternating crops to improve soil fertility and reduce pest buildup. No-till farming minimizes soil disturbance, preserving organic matter and soil structure.

Cover cropping utilizes plants to protect the soil during periods when it would otherwise be bare, preventing erosion and adding nutrients. Afforestation and reforestation – planting trees – stabilize soil and prevent wind erosion. Implementing these strategies is vital for maintaining healthy, productive soils for future generations.

C. Importance of Soil Health

Healthy soil is the foundation of thriving ecosystems and sustainable agriculture, playing a critical role in global food security. It’s far more than just dirt; it’s a complex living system teeming with microorganisms, organic matter, and minerals. Soil health directly impacts plant growth, providing essential nutrients, water retention, and physical support.

Healthy soils also filter water, reducing pollution and replenishing groundwater supplies. They sequester carbon, mitigating climate change, and support biodiversity, providing habitats for countless organisms. Poor soil health leads to erosion, reduced crop yields, and increased reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

Maintaining soil health is crucial for long-term environmental sustainability and human well-being. Understanding its composition and implementing conservation strategies are essential components of responsible land management.